Help Us Pass Federal Farm Legislation!

What You’ll Learn From This Report

- 1: Report findings

- A nationwide water shutoff moratorium might have saved more than 9,000 lives and prevented nearly half a million people from being infected with COVID-19 through the end of 2020.

- 2: A national water affordability crisis

- The pandemic has exposed and exacerbated the pre-existing water affordability crisis in the United States.

- 3: Water shutoff moratoria during the pandemic

- A wave of protections and a wave of endangerment provide an opportunity to study outcomes of each approach.

- 4: Our study

- A small change in infection growth rate yields a significant impact.

- 5: Conclusions and recommendations

- 5 specific steps could save countless lives and slow the spread of contagion during public health emergencies.

Part 1:

Report Findings

A nationwide water shutoff moratorium might have saved more than 9,000 lives and prevented nearly half a million people from being infected with COVID-19 through the end of 2020.

This study finds that in states with moratoria, the growth rates for COVID-19 infections and deaths were significantly lower. Had these shutoff protections been in place nationally, it might have reduced total COVID cases by 4.0 percent and COVID deaths by 5.5 percent in the 41 states without a full coverage of a moratorium over the period from April 17, 2020 to December 31, 2020. Existing water shutoff protections have protected human health and helped slow the spread of novel coronavirus.

Since March 2020, when the outbreak of the COVID-19 was declared a national emergency, hundreds of localities and states took strong action to suspend water shutoffs to ensure households had water for handwashing and sanitation. Unfortunately, this patchwork of protections was never uniformly applied nationwide and left millions of people vulnerable to service disruptions due to an inability to pay water bills during the pandemic.

With emerging variants of the virus that causes COVID- 19, it is critical to ensure access to water services to continue to help slow the spread of the virus and prevent worsening infection rates. Food & Water Watch urges President Joe Biden to halt water shutoffs nationally for the remainder of the COVID-19 national emergency, and his administration should champion legislative solutions to cancel the water debt accrued during the pandemic and fully fund our public water infrastructure to provide long-term relief into the future.

Key Findings

From April 17, 2020 to December 31, 2020, states with moratoria on water shutoffs significantly reduced their growth rates of COVID infections and deaths, compared to states without moratoria, with the biggest reduction seen in states with comprehensive water shutoff moratoria covering all water systems in the state. A moratorium on water shutoffs was associated with a reduced daily infection growth rate by 0.235 percent, and daily death growth rate by 0.135 percent. These small reductions in the daily growth rates were significant and had a sizeable impact on the cumulative case and death numbers. Comprehensive water shutoff moratoria that apply to all water systems in a given state are associated with even lower infection and death growth rates. A nationwide water shutoff moratorium might have reduced COVID cases by 3.97 percent and COVID-related deaths by 5.51 percent in the 41 states without full coverage of a moratorium over this period. Extrapolating from model results, we estimated a nationwide water shutoff moratorium during the study period might have protected 480,715 people from COVID-19 infection and 9,052 people from death.

Report by Xue Zhang and Mildred E. Warner from Cornell University in collaboration with Food & Water Watch

Part 2:

A National Water Affordabilty Crisis

The pandemic has exposed and exacerbated the pre-existing water affordability crisis in the United States.

Since March 2020, one of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s top recommendations to help stop the spread of the novel coronavirus has been thorough and frequent handwashing,1 but tens of thousands of people have been unable to follow this simple but crucial advice because their water service was shut off over water debt.2

For years, unaffordable water bills have been a growing problem in communities across the country.3 A 2017 study found that water bills were already unaffordable for 12 percent of households, and if water charges increased at projected rates, nearly 36 percent of U.S. households would be unable to afford their water bills within five years.4 This crisis disproportionately affects low-income households and communities of color.5 A study of Michigan found that communities of color pay higher average household water bills than communities with lower percentages of racial minorities.6

Austerity underlies this crisis. The federal government has cut back support for water systems, shifting the burden onto local ratepayers. Federal funding for water and sewer systems fell by 77 percent in real dollars from its peak in 1977 to 2017.7 At the same time, water pipes are aging and need to be replaced, while treatment plants need updates to comply with stronger water quality regulations, and climate chaos creates unprecedented challenges in many parts of the country.8 With weak federal support, water systems rely on rate increases to meet these daunting challenges.9 But many people just can’t keep up with bills that outpace their wages.

Hardships and Water Shutoffs

One of the main collection practices of utilities for unaffordable water bills is service shutoffs.10 In a more typical year, 2016, an estimated 15 million people experienced a water shutoff for nonpayment.11 A 2015 national survey found only 8 percent of municipalities had programs to protect low-income consumers from water shutoffs, and publicly owned water operators were more likely to protect residents from water shutoffs.12

Water shutoffs pose a real threat to human health.13 Without water service, people cannot flush their toilets, wash their hands or bathe. Lack of adequate sanitation can cause diseases to spread and allow people to become sick. The elderly, pregnant women, children and people with diabetes and other illnesses would be especially vulnerable.14 Black and Indigenous people of color, Latinx communities and low-income populations face higher disconnection rates and are more likely to lack access to basic water services.15 Water shutoffs can be traumatic. There is a substantial, statistically significant effect of water insecurity on psychological distress.16

A January 2021 working paper from Duke University researchers, published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, found that policies that promote housing stability through moratoria on evictions and utility shutoffs can have profound impacts on COVID death and infection rates.17

Part 3:

Water Shutoff Moratoria During the Pandemic

A wave of protections and a wave of endangerment provide an opportunity to study outcomes of each approach.

Before the pandemic, protections from water shutoffs were rare in the United States,18 but on March 9, 2020, Detroit became among the first U.S. cities to pause water shutoffs and temporarily reconnect water services for all residents.19 Advocates had fought water shutoffs in Detroit for nearly two decades before this historic decision,20 which sparked a wave of moratoria nationally. Over the next several months, more than 800 localities and states followed Detroit’s lead.21

A Wave of Protections

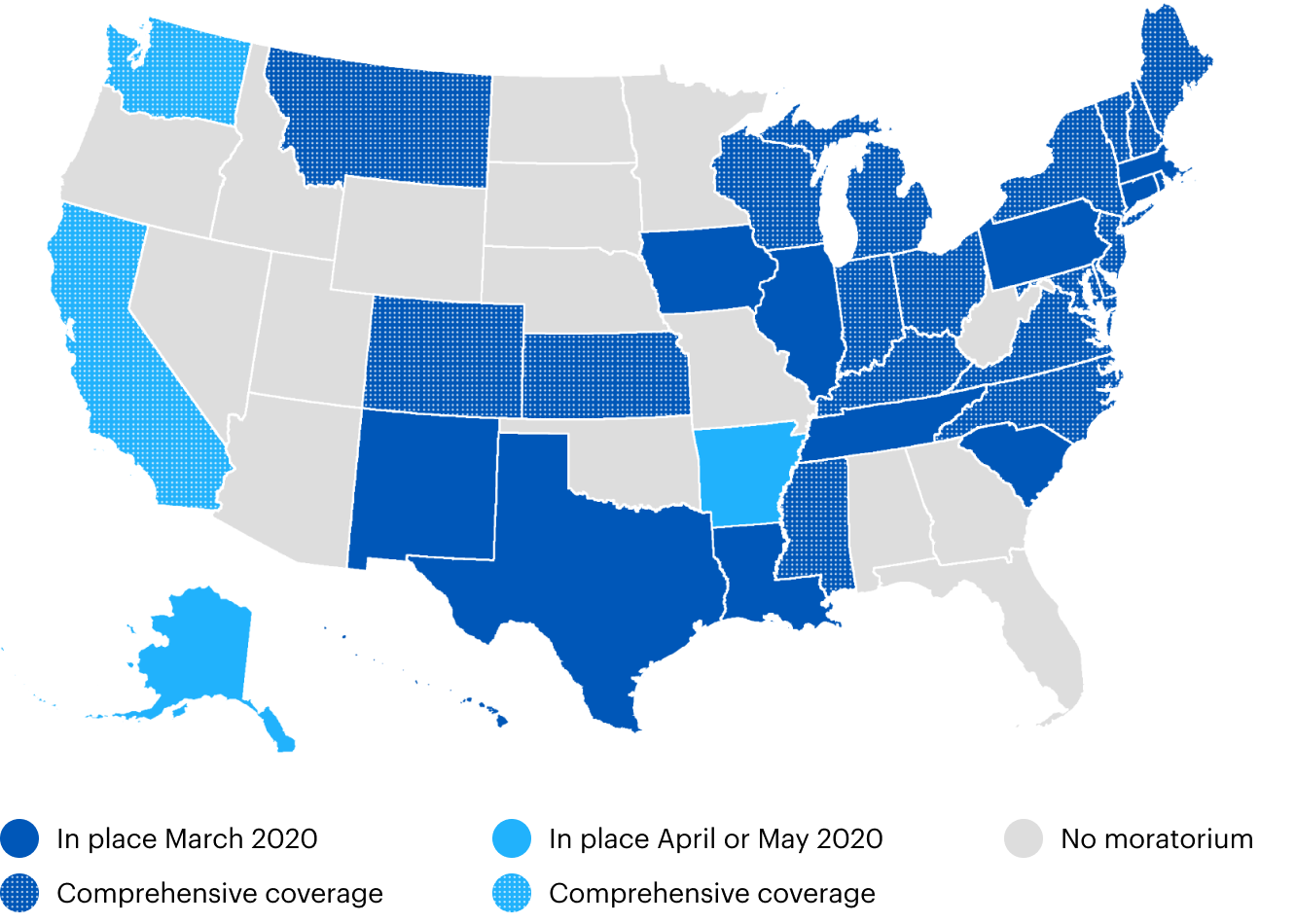

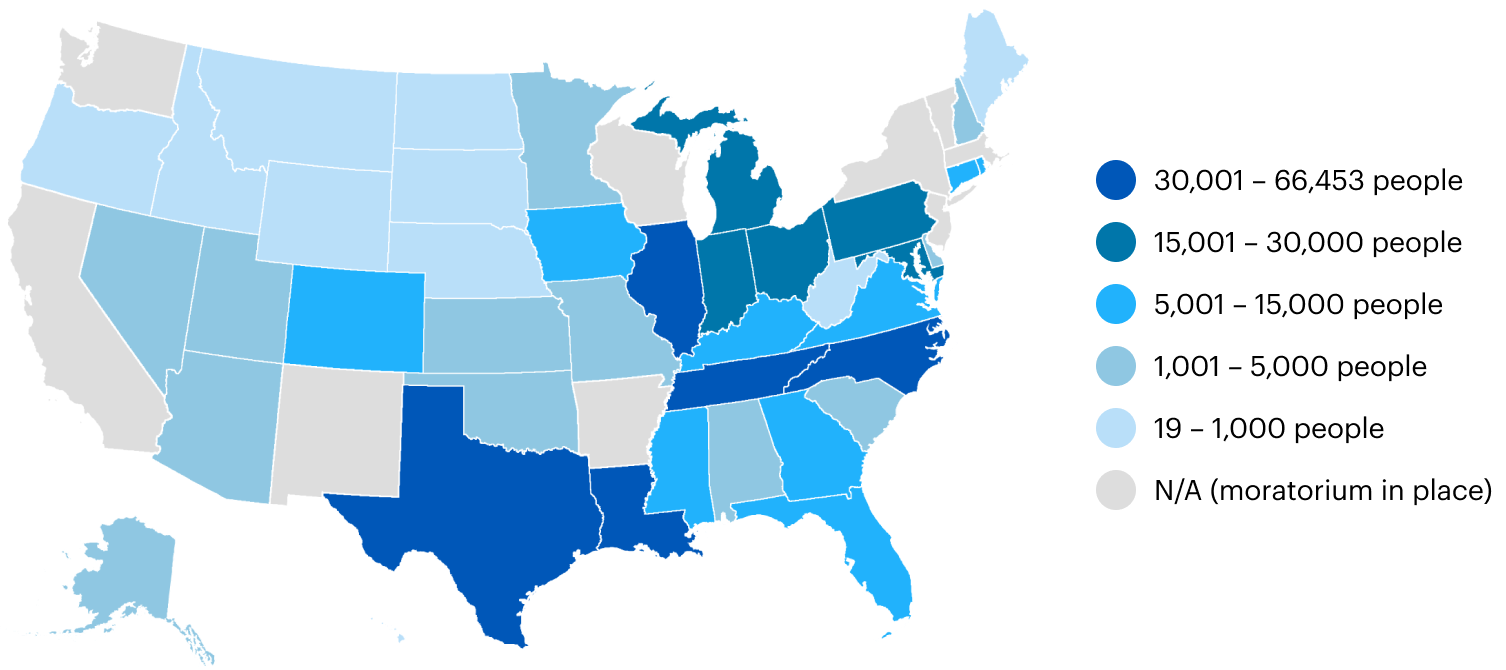

By June 2020, 34 states had imposed moratoria on water shutoffs, protecting the 247 million people living in those states. Twenty states imposed comprehensive water shutoff moratoria that apply to all water systems in the state, and an additional 14 states imposed partial moratoria that covered only water systems, typically investor-owned utilities, that are regulated by state public utility commissions (see Figure 1 and Appendix A).

States that regulate private water utilities through their public utility commission and states that had higher COVID-19 case rates were more likely to impose a moratorium on water shutoffs in the first two months of the COVID-19 pandemic.22 Cities with higher per capita income, a higher percent of people of color, and higher income inequality and Democratic-led states were also more likely to impose moratoria on water shutoffs.23

It is clear that moratoria on water shutoffs have protected hundreds of thousands of people from disconnection. Based on limited data from the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities, 37,386 households — about 100,000 people — in New Jersey alone were protected from losing their water at the end of 2020 because of the state-issued moratoria.24 California found that 1.6 million households (one in eight households) were behind on their water bills, owing more than $1 billion as of January 2021.25

FIGURE 1. State Water Shutoff Moratoria as of May 2020

A Wave of Endangerment

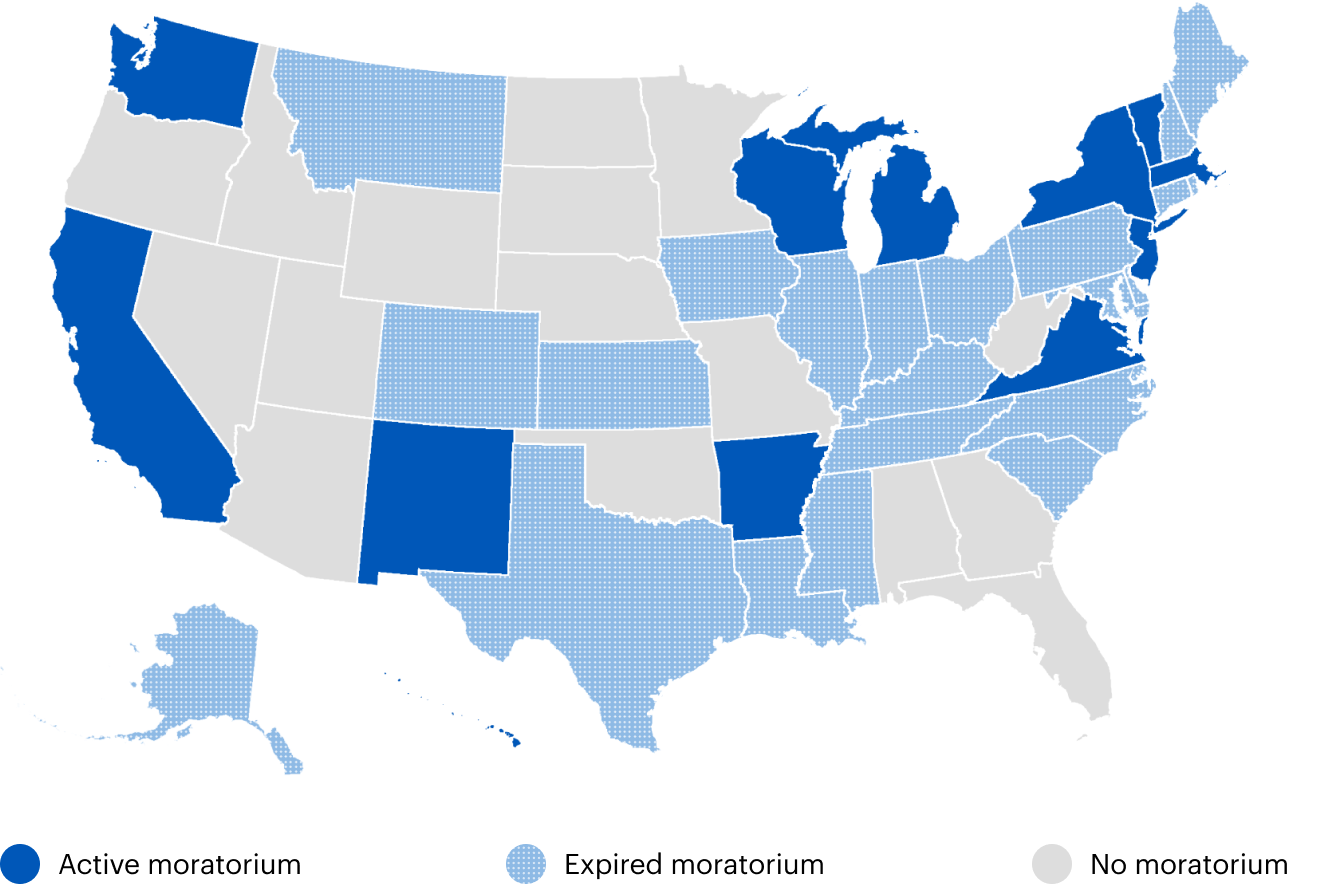

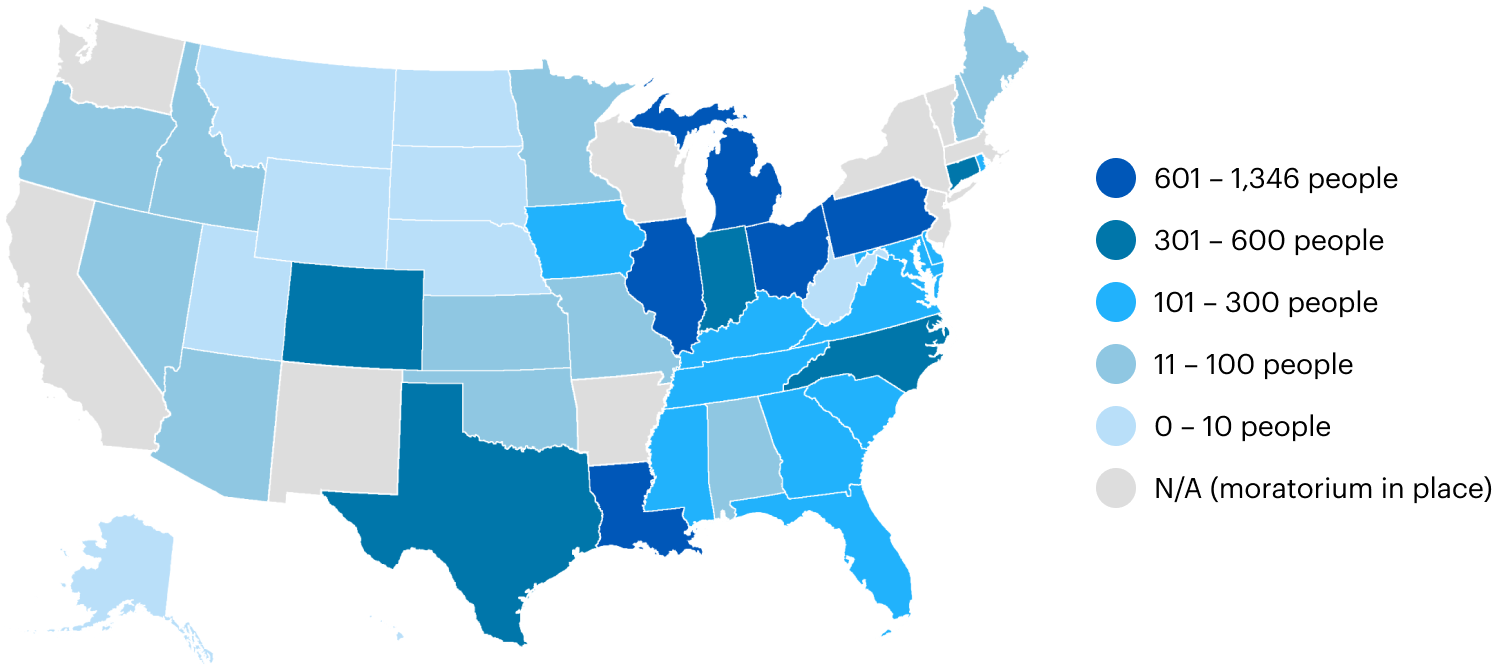

Many of these protections were short-lived and expired months before COVID cases peaked in January 2021. By the end of 2020, 22 states had allowed their moratoria to expire, leading to 134 million people losing protections from water shutoffs. Only 12 states still had moratoria in place by the end of 2020 (see Figure 2 and Appendix A). As of December 2020, 65 percent of the country — 211 million people — were not covered under a state- issued moratorium. This includes 75 million people of color and 2.6 million households in the lowest income quintile. These households are most at risk of water disconnection.

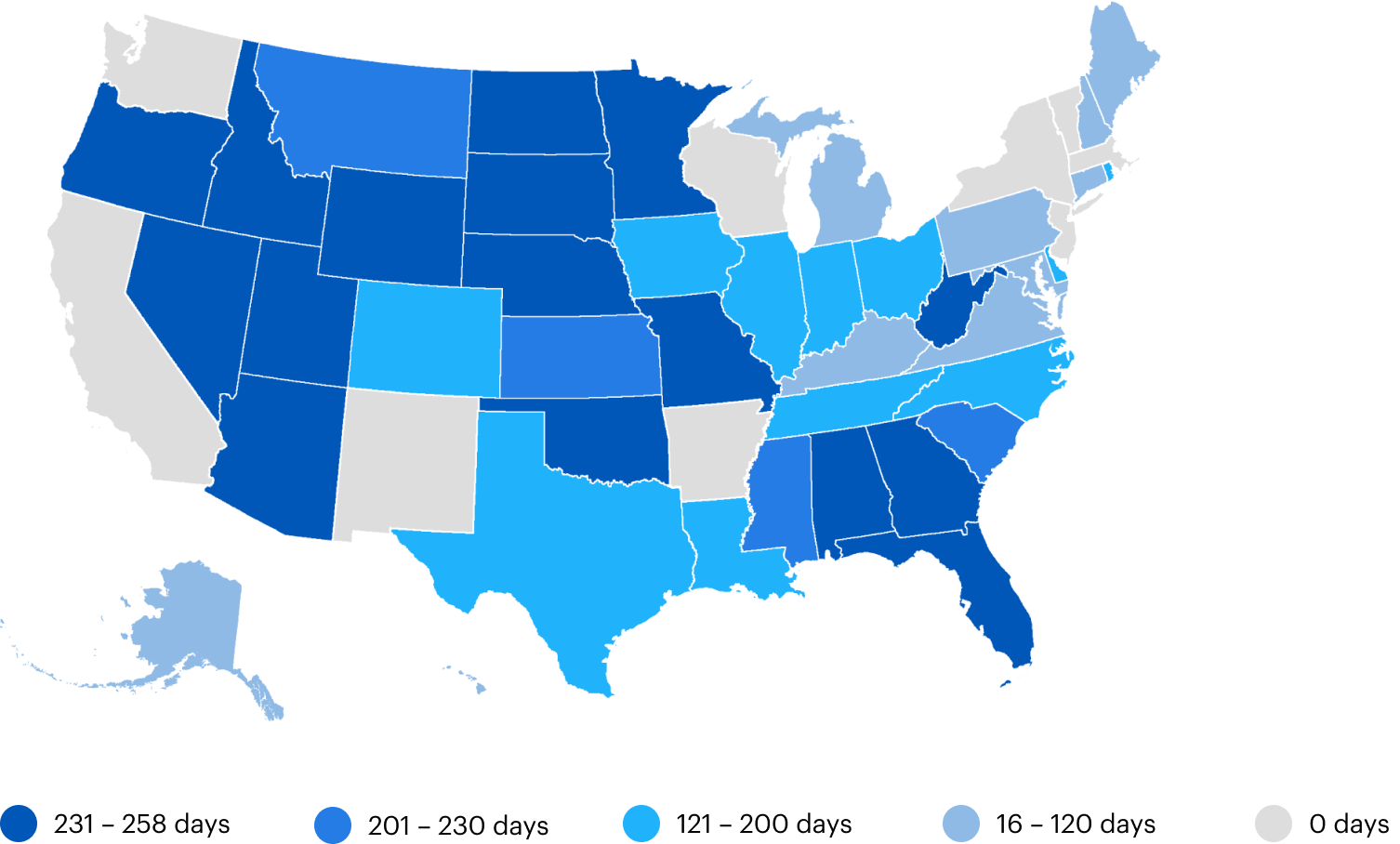

The length of state-imposed moratoria varied greatly across the country (see Figure 3 for the number of days that states went without a moratorium during the study period). During the study period, only nine states had a moratorium in place the entire time. Twenty-five states had a moratorium in place part of the time, and 16 states had no moratorium for the entire period.

FIGURE 2. State Water Shutoff Moratoria as of December 31, 2020

FIGURE 3. Days without a state moratorium on water shutoffs during the study period (April 17 -December 31, 2020)

In Michigan, for example, Governor Whitmer issued a comprehensive statewide water restoration order and moratorium on March 28, 2020.26 The order, as extended, was set to remain in effect until at least the end of the year, but in October, the state Supreme Court struck down many of the Governor’s COVID protections, including the shutoff moratorium.27 Figure 4 shows that cases were peaking, due to the second wave, in the days when the moratorium was not in effect. Michigan water advocates successfully passed state legislation to reimpose a moratorium, which went into effect in December 2020.28

FIGURE 4. COVID-19 cases and water shutoff moratoria over time in Michigan (February – December 2020)

Part 4:

Our Study

A small change in infection growth rate yields a significant impact.

Study Design

We ran a multilevel mixed effects linear regression to examine the relation between water shutoff moratoria and COVID-19 daily infection growth rate and daily death growth rate between April 17 and December 31, 2020.29 This method has been used in other studies of COVID-19 health policies.30 Both the COVID-19 infection growth rate and death rate had a large fluctuation at the beginning of the pandemic in March due to the low initial denominator of cases, so we excluded these outliers.

We calculate growth rate in confirmed cases and deaths using the prior seven-day rolling average. This smooths spikes and reporting fluctuations (e.g., weekends) to more accurately estimate the trend. Our model controls for the effect of time to get an overall effect of the moratoria.

Because the infection rate is related to testing capacity which varies across states, we controlled for the daily test growth rate in the infection growth rate model. We also controlled for comprehensive coverage of the moratoria (applied to all water systems), and other confounding factors that might affect COVID case rates, including other state policies, such as mask mandates, the level of health insurance coverage and state demographic characteristics, such as minorities and essential workers.31

Results: Significant Decrease in COVID Infections and Deaths with Moratoria

Model results show that for the days when states had

a moratorium on water shutoff in place, daily infection growth had a 0.235 percent decrease and the death growth rate had a 0.135 percent decrease (see Appendix 2). In addition, comprehensive coverage of the moratorium was significantly associated with an even lower infection and death growth rate. This small change in the growth rate had a significant impact.

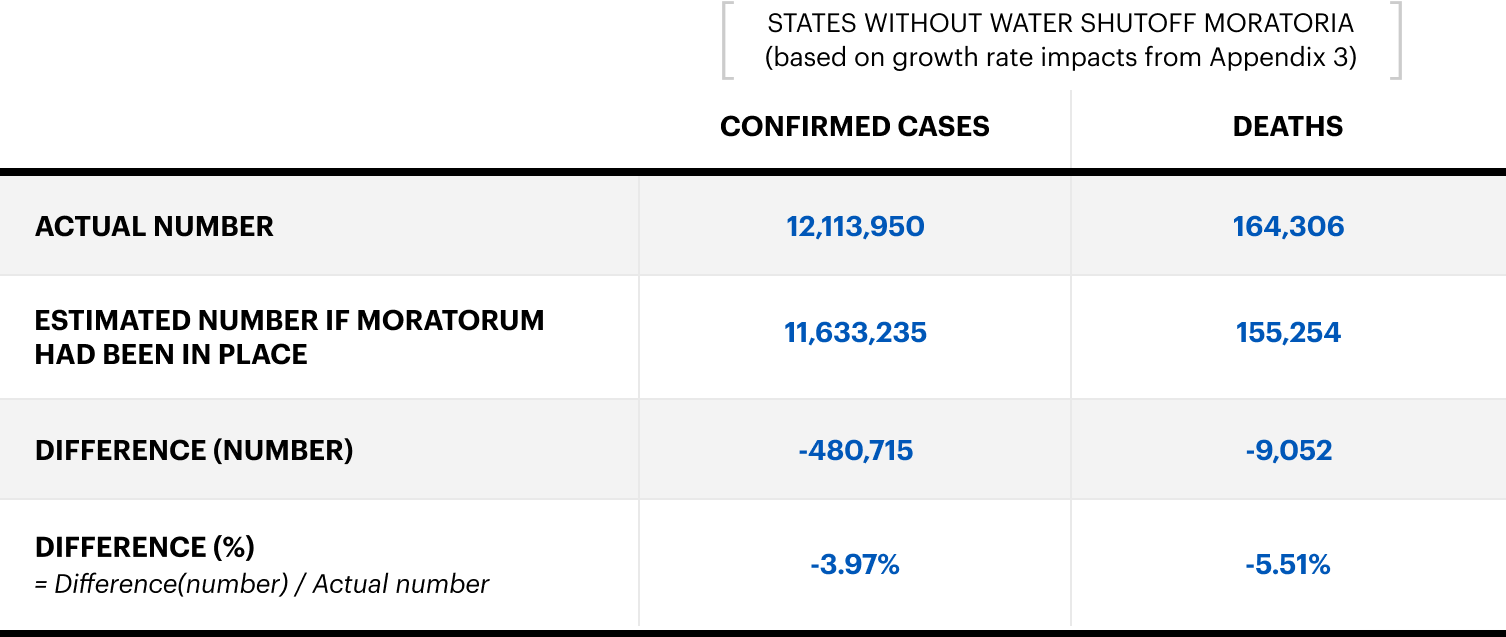

Protecting 9,000 Lives and Preventing Nearly Half A Million Infections

Had a national shutoff moratorium been in place during the study period, it might have protected 480,715 people from COVID-19 infection and 9,052 people from death. This accounts for 4.0 percent of the increase in confirmed cases and 5.5 percent of the increase in total deaths for the 41 states which had days without a moratorium during the study period. Using model results, we calculate the potential impacts as shown in Table 1 (see Appendix 3 for calculation). These estimates exclude the 9 states which had a moratorium in place (whether partial or comprehensive) during the entire study period. Partial moratoriums cover less of the population; but in the analysis below, we do not distinguish partial and comprehensive, we only measure days when a moratorium was not in place.

TABLE 1. Potential reduction in COVID-19 cases and deaths if water shutoff moratoria in place across all U.S. States (April 17 – Dec 30, 2020)

Figure 5 illustrates the number of people in each state that might have avoided contracting COVID had a moratorium been in place. Figure 6 shows the number of lives in each state that might have been saved with a nationwide water shutoff moratorium. The biggest benefits are in states with short or no moratoria, and also reflect the state’s relative population size.

FIGURE 5. Number of people who might have been protected from COVID-19 infection by a shutoff moratorium (April 17 -December 31, 2020)

FIGURE 6. Number of people who might have been protected from COVID-19 death by a shutoff moratorium (April 17 -December 31, 2020)

Part 5:

Conclusions and

Recommendations

5 specific steps could save countless lives and slow the spread of contagion during public health emergencies.

A nationwide water shutoff moratorium might have reduced COVID infections by 4.0 percent and by 5.5 percent in states that lacked moratoria. Through a patchwork of protections in states with existing moratoria on water shutoffs, the growth rate of both COVID infections and deaths was significantly lower, with the biggest protection observed in states that imposed comprehensive moratoria on both public and private water systems. A national moratorium might have saved thousands of people. To ensure protection of water access for every person in the country, Food and Water Watch recommends that President Joe Biden work with Congress to:

Enact a Nationwide Moratorium on Utility Shutoffs for the Remainder of the COVID-19 Emergency.

Enacting a nationwide moratorium on utility shutoffs is an important and urgent measure to help slow the spread of COVID-19. There should be policies in place to automatically impose a water shutoff moratorium during states of emergency in the future. Moreover, vulnerable households must be protected from shutoff at all times. This includes households with young children, seniors, and medically compromised individuals.

Cancel Water Debt

Households have accrued an estimated nearly $9 billion in water and sewer debts over the pandemic.32 Federal support is necessary to offer forgiveness of these debts to avoid a tidal wave of shutoffs when moratoria expire.

Establish Income-Based Water Affordability Programs

Federal funding should support the establishment of state and local programs to provide percentage-of-income payment plans with arrears management components for all households at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty level. Combined water and wastewater bills should not exceed 3 percent of household income, according to the United Nation’s standard of water affordability.33

Collect Better Data

Better data collection and reporting are necessary to help inform policy and solutions. Utilities should periodically report statistics about shutoffs, restorations, arrears, aging of arrears, and other metrics to inform policy. These data must be provided by zip code or census tract to allow for investigation of disparate impacts based on race and other socioeconomic factors and to better inform the outreach of low-income aid providers.

Restore Federal Funding for Water Infrastructure

National support for long-term financing for water utilities would help address systemic inequalities and create stronger, more resilient and more equitable communities. The nation’s water and wastewater systems need federal support.34 The Water Affordability, Transparency, Equity and Reliability (WATER) Act is the type of sweeping legislation needed to address water contamination, affordability, job creation and justice all at the same time.

Water must be a priority for an infrastructure stimulus. With adequate water funding, we can provide immediate relief to households and fight the coronavirus, and we can also protect the health and safety of all communities. We must come out of this crisis with a newfound commitment to providing universal access to water for all.

Tell President Biden: No water shutoffs during a pandemic!

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the Atkinson Center for a Sustainable Future for partial funding support of the Cornell research.

Report by Xue Zhang and Mildred E. Warner from Cornell University in collaboration with Food & Water Watch.100

Endnotes

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “How

to Protect Yourself & Others.” February 4, 2021, available

at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent- getting-sick/prevention.html; Thebault, Reis et al. “How to prepare for coronavirus in the U.S.” Washington Post. March 11, 2020. - For example, see: Missouri Public Service Commission. “Staff report on utility data request responses.” File No. AW- 2020-0356. February 22, 2021 at 34; Tennessee American Water. “Informational filing of Tennessee-American Water Company.” Tennessee Public Utility Commission. Docket No. 20-00047. February 15, 2021 at 4 to 8; Illinois Commerce Commission. “Illinois American Water Compliance Filing.” Docket 20-0309. February 16, 2021 at 2; Grant, Robert. “‘Some families end up homeless’: Jacksonville advocacy group urges utility districts to stop disconnects during pandemic.” Action Jax News. October 8, 2020.

- National Academy of Public Administration. “Developing a New Framework for Community Affordability of Clean Water Services.” October 2017 at 2.

- Mack, Elizabeth A. and Sarah Wrase. “A burgeoning crisis? A nationwide assessment of the geography of water afford- ability in the United States.” PLoS One, Vol. 12, Iss. 1. January 2017 at 7 to 9.

- Montag, Coty. Thurgood Marshall Institute at the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. “Water/Color: A study of race and the affordability crisis in America’s cities.” 2019 at 2 to 5.

- Butts, Rachel and Stephen Gasteyer. “More cost per drop: Water rates, structural inequality, and race in the United States — The case of Michigan.” Environmental Reviews & Case Studies, Vol. 13, No. 4. December 2011 at 386 and 392.

- U.S. Congressional Budget Office. “Public Spending on Transportation and Water Infrastructure, 1956 to 2017.” (Pub. No. 54539). October 2018 at Supplemental Table W-8.

- Mirosa, Oriol. “Water affordability in the United States: An initial exploration and an agenda for research.” Sociological Imagination. Vol. 51, Iss. 2. December 2015 at 41 to 42.

- National Academy of Public Administration at 25.

- U.S. EPA. Environmental Financial Advisory Board. “Afford- able Rate Design for Households.” February 2006 at 5.

- Food & Water Watch. “America’s Secret Water Crisis: Na- tional Shutoff Survey Reveals Water Affordability Emergency Affecting Millions.” October 2018 at 2.

- Homsy, George C. and Mildred E. Warner. “Does public ownership of utilities matter for local government water poli- cies?” Utilities Policy. Vol. 64. Iss. 101057. 2020 at 1 and 5.

- Amirhadji, Jason et al. Georgetown Law Human Rights Insti- tute Fact-Finding Practicum. “Tapped Out — Threats to the Human Right to Water in the Urban United States.” April 2013 at 31 to 32.

- Ibid. at 31 to 32.

- Holmes, Lillian et al. Pacific Institute. “Water and the COV- ID-19 Pandemic: Equity Dimensions of Utility Disconnections in the U.S.” July 2020 at 3 to 4; DigDeep and US Water Alliance. “Closing the Water Gap in the United States: A National Action Plan.” 2019 at 22; Montag, 2019 at 4.

- Gaber, Nadia et al. “Water insecurity and psychosocial distress: case study of the Detroit water shutoffs.” Journal of Public Health. 2020 at 1.

- Jowers, Kay et al. “Housing Precarity & the COVID-19 Pan- demic: Impacts of Utility Disconnection and Eviction Mora- toria on Infections and Deaths Across US Counties.” National Bureau of Economic Research. January 2021. Available at https://www.nber.org/papers/w28394.

- Homsy and Warner, 2020.

- Neavling, Steve. “As coronavirus spreads, Detroit to restore water to thousands of households, offer moratorium on shutoffs.” Detroit Metro Times. March 9, 2020; Lakhani, Nina. “Detroit suspends water shutoffs over Covid-19 fears.” The Guardian. March 12, 2020.

- People’s Water Board Coalition. (Press release). “People’s Water Board Coalition Applauds Detroit Mayor’s Decision to Ban Water Shutoffs and Restore Residential Water.” Decem- ber 8, 2020.

- Food & Water Watch. “External-Local-State Water Shutoff Moratoria Amidst Coronavirus.” Accessed March 5, 2021, available at https://docs.google.com/ spreadsheets/d/153Ze6RRZ-ZZ9oVkaSErhVHGMv3Z4laQDs- 0GRO7UmYnQ.

- Warner, Mildred E., Xue Zhang and Marcela González Rivas. ”Which states and cities protect residents from water shut- offs in the COVID-19 pandemic?” Utilities Policy. Vol. 67. Iss. 101118. September 2020 at 1, 3 to 4.

- Ibid. at 4.

- New Jersey Board of Public Utilities. “Water and Sewer Ar- rearages as of December 2020.” 2021, available at https:// www.nj.gov/bpu/newsroom/reports/covid19/Water%20 and%20Sewer%20Arrearages%20December%202020%20 Summary.pdf; U.S. Census. “Quickfacts: New Jersey.” Avail- able at https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/NJ. Accessed March 5, 2021.

- California Water Boards. “Frequently Asked Questions: COVID-10 Drinking Water Financial Impacts Survey Results.” January 19, 2021 at 2.

- Michigan. Executive Order No. 2020-28. March 28, 2020.

- Egan, Paul. “Michigan Supreme Court strikes down Gov. Whitmer’s emergency orders, effectively immediately.” Detroit Free Press. October 12, 2020.

- Michigan. Public Acts of 2020. Act No. 252. December 22, 2020.

- New York Times. “The COVID Tracking Project. Social Ex- plorer.” 2020. Available at https://www.socialexplorer.com. Accessed January 25, 2021.

- Zhang, Xue and Mildred W. Warner. “COVID-19 Policy Differences across US States: Shutdowns, Reopening, and Mask Mandates.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. Vol. 17. Iss. 24. December 2020 at 9520; Lyu, Wie and George L. Wehby. “Shelter-In-Place Orders Re- duced COVID-19 Mortality and Reduced The Rate Of Growth In Hospitalizations.” Health Affairs, Vol. 39. Iss. 9. September 2020 at 1615 to 1623; Lyu, Wu & George L. Wehby. “Com- munity Use Of Face Masks And COVID-19: Evidence From A Natural Experiment Of State Mandates In The US.” Health Affairs, Vol. 39. Iss. 8. June 2020 at 1419 to 1425.

- U.S. Census. “American Community Survey (2015–2019).” Prepared by Social Explorer. 2020. Available at https://www.socialexplorer.com. Accessed January 25, 2020; Ballotpedia. “State-level mask requirements in response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, 2020- 2021.” 2021. Available at https://ballotpedia.org/State-level_ mask_requirements_in_response_to_the_coronavirus_ (COVID-19)_pandemic,_2020-2021. Access on February 15, 2021; Broaddus, Matt. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “5 Million Essential and Front-line Workers Get Health Cover- age through Medicaid.” August 4, 2020.

- National Association of Clean Water Agencies. “Recovering from Coronavirus: Mitigating the Economic Cost of Maintain- ing Water and Wastewater Service in the Midst of a Global Pandemic and National Economic Shut Down.” 2020. Available at https://www.nacwa.org/docs/default-source/ resources—public/water-sector-covid-19-financial-impacts. pdf.

- United Nations, United Nations Habitat, and World Health Organization. “The Right to Water.” Fact Sheet No. 35. August 2010 at 11.

- American Society of Civil Engineers. “2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure.” December 2020 at 35 to 38 and 152 to 157. Available at https://infrastructurereportcard.org.

- Laws of Alaska. Enrolled SB 241. §19 and §39. (2020).

- Arkansas Public Service Commission. Order. Docket No. 20- 012-A. Order No. 1. April 10, 2020 at 2 to 3.

- California Public Utilities Commission. (Press release). “CPUC ensures essential utility services for consumers to assist in Covid-19 mitigation.” March 17, 2020.

- California. Executive Order N-42-20. April 2, 2020.

- Colorado. Executive Order D 2020-012. March 20, 2020.

- Colorado. Executive Order D 2020-031. April 6, 2020; Colo- rado. Executive Order D 2020-051. April 30, 2020; Colorado. Executive Order D 2020-088. May 29, 2020; Colorado. Executive Order. D 2020-098. June 12, 2020. (EO-088 expires 15 days from May 29. The June 12 order includes no moratorium).

- Connecticut Public Utilities Regulatory Authority. Motion 1. Docket No. 20-03-15. March 12, 2020.

- Connecticut Public Utilities Regulatory Authority. Motion 9. Docket No. 20-03-15. September 2, 2020 at 5.

- Delaware. Executive Order. Sixth Modification of the Declara- tion of a State of Emergency for the State of Delaware due to a Public Health Threat. March 24, 2020 at 8 to 9.

- Delaware. Executive Order. Twenty-Third Modification of the Declaration of a State of Emergency for the State of Dela- ware due to a Public Health Threat. June 30, 2020 at 12.

- Hawaii Public Utilities Commission. Order 37125. Non-dock- eted. May 4, 2020 at 4; Hawaii Public Utilities Commission. Order 37506. Docket No. 2020-0209. December 22, 2020 at 2 to 3.

- Illinois Commerce Commission. “Emergency Interim Order.” Docket No. 20-0309. March 18, 2020 at 7.

- Illinois Commerce Commission. “Staff of the Illinois Com- merce Commission’s Unopposed Motion for Entry of an Order Approving and Adopting Stipulation Resolving All Issues Between Various Parties.” Docket No. 20-0309. June 10, 2020 at 5 and 8; Illinois Commerce Commission. “Stipu- lation.” Docket No. 20-0309. June 10, 2020 at 2 and 3 (30 days after August 1 are under moratorium period).

- Indiana. Executive Order 20-05. March 19, 2020 at 2.

- Indiana. Executive Order 20-33. June 30, 2020 at 2.

- Iowa Utilities Board. “Order Phasing in Disconnection of Utility Service and Modifying March 27 2020 Order.” Docket No. SPU-2020-0003. May 20, 2020 at 1 to 3.

- Kansas. Executive Order No. 20-05. March 17, 2020.

- Kansas. Executive Order No. 20-28. April 30, 2020.

- Kentucky Public Service Commission. Order. Case No. 2020- 00085. March 16, 2020 at 3 and 8.

- Kentucky. Executive Order No. 2020-323. May 8, 2020 at 3.

- Kentucky Public Service Commission. Order. Case No. 2020- 00085. September 21, 2020 at 6.

- Kentucky. Executive Order 2020-881. October 19, 2020 at 2 and 4.

- Louisiana Public Service Commission. Executive Order. March 13, 2020.

- Louisiana Public Service Commission. Special Order No. 43- 2020. July 1, 2020 at 2.

- Maine Public Utilities Commission. Order. Docket No. 2020- 00081. March 16, 2020.

- Maine Public Utilities Commission. Order. Docket No. 2020- 00081. September 17, 2020 at 1.

- Maryland. Order of the Governor of the State of Maryland Prohibiting Termination of Residential Services and Late Fees. March 16, 2020.

- Maryland. Order of the Governor of the State of Maryland. No. 20-07-31-01. July 31, 2020.

- Maryland Public Service Commission. Order on Covid-19 emergency measures. ML 231904. PC53. September 22, 2020 at 3.

- Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities. “Chairman’s first set of orders under G.L. c. 25, § 4B.” March 24, 2020; Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities. “Chairman’s eighth set of orders under G.L. c. 25, § 4B.” February 26, 2021.

- Michigan. Executive Order No. 2020-28. March 28, 2020.

- Michigan. Public Acts of 2020. Act No. 252. December 22, 2020.

- Egan, Paul. “Michigan Supreme Court strikes down Gov. Whitmer’s emergency orders, effectively immediately.” De- troit Free Press. October 12, 2020.

- Mississippi Public Service Commission. Clarification State- ment. Docket No. 2018-AD-141. March 19, 2020.

- Mississippi Public Service Commission. Order Extending Order Temporarily Suspending Disconnection of Certain Util- ity Services. Docket No. 2018-AD-141. May 12, 2020 at 5.

- Montana. Directive Implementing Executive Orders 2-2020 and 3-2020 providing measures to limit foreclosures, evic- tions, and disconnections from service. March 30, 2020 at 4.

- Montana. Directive Implementing Executive Orders 2-2020 and 3-2020 and establishing conditions for Phase Two. May 19, 2020 at 3.

- New Hampshire. Emergency Order #3 Pursuant to Executive Order 2020-04. March 17, 2020.

- New Hampshire. Emergency Order #58 Pursuant to Execu- tive Order 2020-04. June 30, 2020.

- New Hampshire Public Utilities Commission. “Agreement.” IR 20-089. September 8, 2020 at 5.

- New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, Department of Environmental Protection, and Board of Public Utilities. (Press release). “All water providers asked to suspend shut- offs during Covid-19 outbreak.” March 20, 2020; Hutter, David. “Murphy orders water providers to suspend shut-offs during COVID-19.” March 26, 2020.

- New Jersey. Executive Order No. 190. October 15, 2020 at 3, 5 and 6.

- New Mexico Public Regulation Commission. Order Finding Need for the Adoption and Issuance of an Immediate Temporary Emergency Rule Prohibiting the Discontinuation of Residential Customer Utility Service. Case No. 20-00069- UT. March 18, 2020 at 5; NMAC. §17.12.760.10(B)(1). Novem- ber 10, 2020.

- New York Department of Public Service. (Press release). “Utilities to suspend disconnections for households facing hardships during COVID-19 outbreak.” March 13, 2020.

- Laws of New York State. Chapter 108. (2020).

- North Carolina. Executive Order No. 124. March 31, 2020 at 4.

- North Carolina. Executive Order No. 142. May 30, 2020 at 7.

- Ohio Environmental Protection Agency. Director’s Final Findings and Orders. In the Matter of Public Water Systems Under ORC Chapter 6109. March 31, 2020 at 2.

- Ohio Environmental Protection Agency. “Termination of the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency’s March 31, 2020 State of Emergency Public Water System Order (PWS Or- der).” July 10, 2020.

- Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission. Emergency Order. Docket No. M-2020-3019244. March 13, 2020 at 2.

- Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission. Order. Docket No. M-2020-3019244. October 8, 2020 at 3.

- Rhode Island Public Utilities Commission. Order on Commission’s Own Motion. Docket No. 5022. March 17, 2020 at 4.

- Rhode Island Public Utilities Commission. Order. Docket No. 5022. July 15, 2020 at 4.

- South Carolina Public Service Commission. Commission Di- rective. Order No. 2020-228. Docket No. 2020-106-A. March 18, 2020.

- South Carolina Public Service Commission. Commission Directive. Order No. 2020-374. Docket No. 2020-106-A. May 14, 2020.

- Tennessee Public Utility Commission. (Press release). “TPUC Order on Service Disconnections.” March 27, 2020.

- Tennessee Public Utility Commission. “Order Lifting Suspen- sion of Disconnections of Service for Lack of Payment with Conditions, Effective on August 29, 2020.” Docket No. 20- 00047. September 16, 2020 at 2.

- Texas Public Utility Commission. Order Directing Certain Actions and Granting Exceptions to Certain Rules. Project No. 50664. March 26, 2020 at 1 and 2.

- Texas Public Utility Commission. Third Order Directing Certain Actions and Granting Exceptions to Certain Rules. Project No. 50664. May 14, 2020 at 1 and 2.

- Vermont. No. 92 of 2020 (H. 681) §9. March 30, 2020 at 7 to 8.

- Virginia State Corporation Commission. Order Suspending Disconnection of Service and Suspending Tariff Provisions Regarding Utility Disconnections of Service. Case No. PUR- 2020-00048. March 16, 2020.

- Virginia. 2020 Special Session. Acts of Assembly. Chapter 56. §4-14.7.a. November 18, 2020 at 363.

- Virginia State Corporation Commission. Additional Order on Moratorium. Case No. PUR-2020-00048. September 15, 2020 at 2.

- Washington. Proclamation by the Governor. 20-23.2. April 17, 2020 at 4; Washington. Proclamation by the Governor. 20- 23.13. December 8, 2020 at 3.

- Wisconsin Public Service Commission. (Press release). “PSC tells Wisconsin utilities to suspend disconnections for non- payment during public health emergency.” March 13, 2020; Wisconsin Public Service Commission. Supplemental Order on Residential Disconnection – Third. 5-UI-120. October 29, 2020 at 6.

- Zhang, Xue, Warner, Mildred E. and Grant, Mary. 2021 “Water shutoff moratoria lowered COVID-19 infection and death across US States,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine. forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.07.006